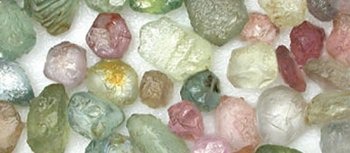

Yogo Sapphires, found only in a single deposit in central Montana, are renowned for their naturally vivid blue and violet hues, as well as their exceptional clarity, requiring no heat treatment to enhance their brilliance. In contrast, Montana Sapphires, primarily mined in the western part of the state, come in a variety of colors, including blue, green, yellow, and pink. Many of these sapphires undergo heat treatment to improve their color and clarity. These remarkable gemstones are part of Montana’s rich mineral wealth, earning it the nickname "The Treasure State."

Yogo Sapphire Jewelry

Engagement RingsRings

Necklaces

Earrings

Bracelets

Vintage Jewelry

Men's Jewelry

All Yogo Jewelry

SHOP GEMSTONES

Shop Loose YogosLearn About Yogos

HistoryGemology

Uniquely Montana

Find Yogo Engagement RingsMontana Sapphire Jewelry

Engagement RingsRings

Necklaces

Earrings

Bracelets

Vintage Jewelry

Men's Jewelry

All MT Sapphire Jewelry

SHOP GEMSTONES

Shop Loose MT SapphiresLearn About Montana Sapphires

HistoryGemology

A True Treasure

Find Montana Sapphire Engagement Rings

History of Yogo Sapphires

Little Blue Pebbles

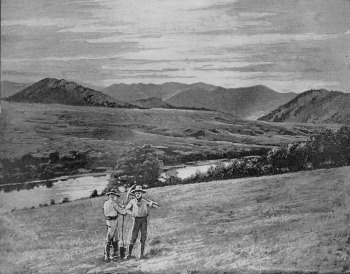

Early Montana prospectors

In 1895, prospector Jake Hoover discovered gold along Yogo Creek in Montana’s Little Belt Mountains. Believing the area held great potential, he partnered with Simon Hobson and Jim Bouvet to establish a mining operation, securing $40,000 in capital. Like many fortune-seekers of the gold rush era, Hoover hoped to strike it rich. However, after a year of mining, the trio had uncovered only 40 ounces of gold—worth a mere $700—and a handful of small blue stones caught in their sluice box. While other miners dismissed these pebbles as worthless, Hoover gathered them, eventually filling a cigar box. Curious about their value, he sent the box to Tiffany & Co. in New York for identification.

The English Mine

One of America’s leading gem experts at the time, Dr. George F. Kuntz, examined the pebbles and identified them as remarkably high-quality natural Sapphires. Impressed by their exceptional color, clarity, and brilliance, Kuntz declared them “the finest precious gemstones ever found in the United States.” Recognizing their value, Tiffany & Co. eagerly sought to acquire the “superbly-colored, gem-quality Sapphires,” sending Hoover a check for $3,750, which was more than five times what he had earned from mining gold at the site.

““In purchasing a mere gold mine, they had acquired the most valuable Sapphire mine in America, yielding more wealth than all the other Sapphire mines in America put together, and a finer quality of gem.” - Dr. George F. Kuntz”

The Sapphires, now known as Yogo Sapphires, turned out to be far more valuable than Hoover and his partners had ever imagined. They were worth more than all the gold Hoover had spent years mining. Realizing their potential, the partners shifted their focus to locating the source of the Sapphires. However, Hoover eventually lost interest in Sapphire mining and sold his shares to his partners. As Dr. Kuntz famously noted, “In purchasing a mere gold mine, they had acquired the most valuable Sapphire mine in America, yielding more wealth than all the other Sapphire mines in America put together, and a finer quality of gem.” This marked the beginning of decades of ownership changes and instability at the Yogo Sapphire Mine.

The British Take Over Hoover's Stake

The English Mine

After selling his shares in what was then called the New Mine Sapphire Syndicate, Hoover’s former partners soon followed. He sold his stake for $5,000, but just two months later, it was resold to the British company Johnson, Walker and Tolhurst, Ltd. for $100,000. The eight lode claims originally staked by Hoover became the foundation of the English Mine. In 1896, two American prospectors claimed six additional sections along the dike in areas Hoover had considered unsuitable for mining, forming the American Mine. For the first half of the 20th century, these two operations were known as the English Mine and the American Mine.

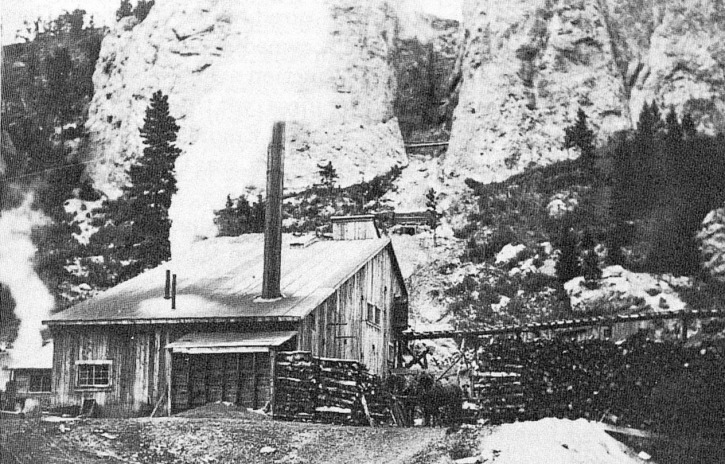

“The early 20th-century operations at the English Mine are regarded as the most successful efforts to commercially mine Yogo Sapphires.”

In 1899, the British company dispatched mining engineer T. Hamilton Walker and his assistant, Charles T. Gadsden, to America to oversee operations, aiming to cut costs and maximize profits. Though not an engineer himself, Gadsden would go on to play a pivotal role in the history of the English Mine. In the early 20th century, the mine thrived, yielding millions of carats of rough Yogo Sapphires.

Original Yogo jewelry by Johnson, Walker & Tolhurst, circa 1920

In an effort to promote Yogo Sapphires internationally, British marketing experts arranged for their exhibition at the Universal Exposition in Paris, where Montana Sapphires received a medal for their exceptional quality and color. However, European retailers soon began marketing them under the name "Orient Sapphires", a label that carried more prestige at the time and commanded higher prices. Because Yogo Sapphires closely resembled these highly sought-after gems, they were often substituted into the market without proper recognition of their true origin.

The early 20th-century operations at the English Mine are considered the most successful commercial mining efforts for Yogo Sapphires. Charles T. Gadsden was appointed as the resident supervisor, overseeing the mine’s daily operations. Despite relying on what were then considered outdated hand-drilling techniques and mule-drawn ore carts, he consistently turned a profit. His expertise set him apart from those running the American Mine, particularly in developing effective methods for separating Sapphires from heavy minerals and preventing miners from stealing the valuable stones. Unfortunately, all the rough Sapphires mined from the English Mine were shipped to London, where most were cut and sold as "Orient Sapphires".

The Two Mines Become One

Washing the ore by hand

Operations at the American Mine were far less successful than those at the English Mine, and ownership changed hands frequently. The cost of developing mining operations often drained investors’ resources, leaving them without enough capital to continue. Unlike the rolling hills of the English Mine, the American Mine was located in steep, rugged cliffs that were more difficult to access. Even when rough Sapphires were extracted, poor cutting techniques and ineffective marketing hindered their commercial success.

By 1913, the Yogo American Sapphire Company, which owned the American Mine at the time, was forced into bankruptcy and listed the dike property for sale at $80,000. Charles T. Gadsden, eager to take full control of the Yogo dike, viewed American mining efforts as inefficient. He traveled to England to persuade the New Mine Sapphire Syndicate, owners of the English Mine, to acquire the American Mine. He argued that the purchase would eliminate competition and quickly pay for itself. Gadsden’s strategy proved correct—by washing the old tailings left behind by previous miners, he recovered over $80,000 worth of Sapphires within the first year, covering the cost of the acquisition before even beginning new operations.

In the early 20th century, the combined Yogo Mine had produced over 13 million carats of rough Sapphires. While many were cut for fine jewelry, others were used as watch bearings in mechanical timepieces. Non-gem-quality stones were sold as abrasives for cutting steel. When World War II increased the demand for industrial abrasives, the Yogo Mine was allowed to continue production, while other mines deemed non-essential were forced to halt operations.

World War and a Flash Flood Take Their Toll

The American Mine hoist

By 1922, the combined Yogo mines began to decline. The introduction of synthetic Sapphires had eliminated the demand for Yogo Sapphires in industrial applications like watch bearings and abrasives, leaving their only value in the gemstone market. After the economic strain of World War I and a period of financial decline, British interest in Yogo Sapphires began to fade. The final blow came in 1923 when a devastating flash flood destroyed much of the mine’s surface infrastructure, including the washing pads, and swept away millions of carats of rough Sapphires. Unwilling to invest further, the British owners put the mine up for sale.

Eventually, the mine was sold for back taxes, passing through the hands of multiple owners. For years, the site remained open, and local residents would visit the area for picnics, collecting small blue pebbles washed downstream by the flood. Many of these stones were later set into jewelry, serving as cherished mementos from a time when anyone could search for Yogos without restriction. Later owners closed off the mine to the public and made various attempts to revive mining and market Yogo Sapphires, but with little success.

The Rise of Roncor

“To this day, several families own property in Sapphire Village and continue small-scale hand mining on their claims.”

In 1969, Herman Yaras of California acquired the Yogo Mine, later selling his interest to fellow Californian Chikara Kunisaki, a celery farmer. The Kunisaki family established Roncor, a company with a plan to generate capital by developing and selling property in a community called Sapphire Village. Roncor sold home sites near the Yogo Mine to rockhounds, granting limited digging rights along the Yogo dike. To this day, several families own property in Sapphire Village and continue small-scale hand mining on their claims.

Roncor attempted to mine the dike from the west at the original American Mine but was unsuccessful. Eventually, they halted operations and put the property up for sale. The mine was then purchased by Intergem, a Colorado-based company, which conducted large-scale strip mining on the eastern end of the dike. During its years of operation, Intergem successfully extracted millions of carats of Sapphires. However, the company was unable to fulfill its purchase agreement with Roncor, resulting in Roncor regaining full ownership of the Yogo Mine.

The AmEx Mine closure

The old English workings

The Vortex Mine hoist

After Intergem’s downfall, the Canadian company Pacific Cascade Sapphires attempted to acquire the Yogo property from Roncor through a mining lease. They secured start-up capital, constructed a wash plant and settling pond, and began searching for Yogo Sapphires. Their efforts included extensive sampling, mapping, and magnetometer testing, but they failed to pinpoint a viable mining location before their funds were depleted and their lease option expired.

Following Pacific Cascade Sapphires, Amex Engineering took on a two-year lease from Roncor. They conducted two bulk sampling operations, one in the middle of the mine and another at the eastern end of the dike. While they recovered a significant number of fine Sapphires, they ultimately chose not to extend their lease. After Amex withdrew, Roncor retained ownership of the property, which remains inactive except for small-scale hand-digging by Sapphire Village residents.

The Vortex Mine: Virgin Territory

The steam-powered hoist at the English Mine, near left

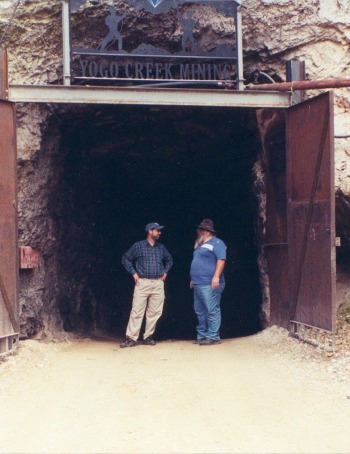

As various companies struggled to find success with the Roncor property, a new mining operation emerged at Yogo Gulch. In January 1984, four local residents—Lanny Perry, Chuck Ridgeway, and their wives, Joy and Marie—made their own discovery. Following a wood-cutting trail, they came across an untouched section of the dike that had previously been dismissed by Gadsden as unworthy of mining. Recognizing its potential, they staked claims on land outside Roncor’s holdings and began their own mining operation. This new site, named the Vortex Mine, was developed as an underground operation. Over time, they sank a shaft 280 feet deep and uncovered two distinct veins of Yogo-bearing ore.

The group successfully operated the mine for several years but recognized the need for additional capital and mining expertise. They leased the operation to Small Mining Development (SMD) of Boise, Idaho, which expanded efforts by driving a spiraling decline shaft to a depth of over 300 feet. SMD experimented with advanced techniques, including high-pressure water jets to extract the ore-bearing rock. However, they ultimately found the mine’s production and profitability unsatisfactory. When SMD withdrew, they dismantled their wash plant, and there was even discussion of permanently sealing the mine by filling the shaft with concrete. By 2004, the Vortex Mine had gone dormant and effectively closed.

The Future of Yogo Sapphires

The future of Yogo Sapphires seemed uncertain until the spring of 2008, when Mike Roberts, a second-generation hard rock gold miner from Alaska, successfully acquired the Vortex Mine and its claims. He revived commercial underground mining at Yogo through the Vortex portal, utilizing the wash plant originally constructed by Pacific Cascade Sapphires.

While the mine’s shaft extended to about 300 feet, previous miners had not thoroughly explored its depths to assess the full extent of Yogo Sapphire deposits. Determined to unlock its potential, Roberts diligently expanded operations, reaching depths of over 400 feet while following a continuous vein of Yogo Sapphires.

The opening portal to the spiral decline of the Vortex Mine

Mike Roberts and Don Baide

The pulsating washing jig and trommel

Tragically, on March 19, 2012, Mike Roberts lost his life in an accident while working underground in the Yogo Sapphire mine. A beloved friend to many, Mike’s presence is deeply missed.

New Beginnings: The Reopening of the Vortex Mine

Aerial view of the Vortex Mine's surface

After Mike’s passing, the Vortex Mine remained closed for nearly five years, leaving its future uncertain. However, in the summer of 2017, the Baide family proudly acquired the mine and immediately set plans in motion to restore it to full operation. Under their ownership, the Vortex Mine operated as an eco-friendly and highly professional venture, impacting fewer than five acres above ground with minimal surface disturbance. Accessed via a 35-story-deep spiral decline, the mine is run by a skilled team of six experienced Montana miners.

Vortex Mine Entrance

This reopening came at a time when Yogo Sapphires had become increasingly difficult to acquire. Don Baide, father of Jason Baide, saw an opportunity not only to continue Mike’s legacy but to ensure Montana had a sustainable source of natural Yogo Sapphires. His efforts positioned Gem Gallery as the premier supplier of these rare gems, benefiting jewelers and customers seeking a Sapphire deeply rooted in Montana’s history. The Sapphires mined from the Vortex Mine were distributed under the Yogo Mining Company LLC.

As of 2024, the Vortex Mine is no longer operational, making Yogo Sapphires even rarer. While the mine may reopen in the future, its closure has further limited the availability of these sought-after gems. Today, Gem Gallery, under Jason Baide’s leadership, continues to champion Yogo Sapphires, ensuring their legacy and significance endure.

Summary material courtesy of "Yogo: The Great American Sapphire," Stephen M. Voynick, Mountain Press Publishing Co., Missoula MT, 1985.